- Tokyo: 01:04

- Singapore: 00:04

- Dubai: 20:04

- London: 16:04

- New York: 11:04

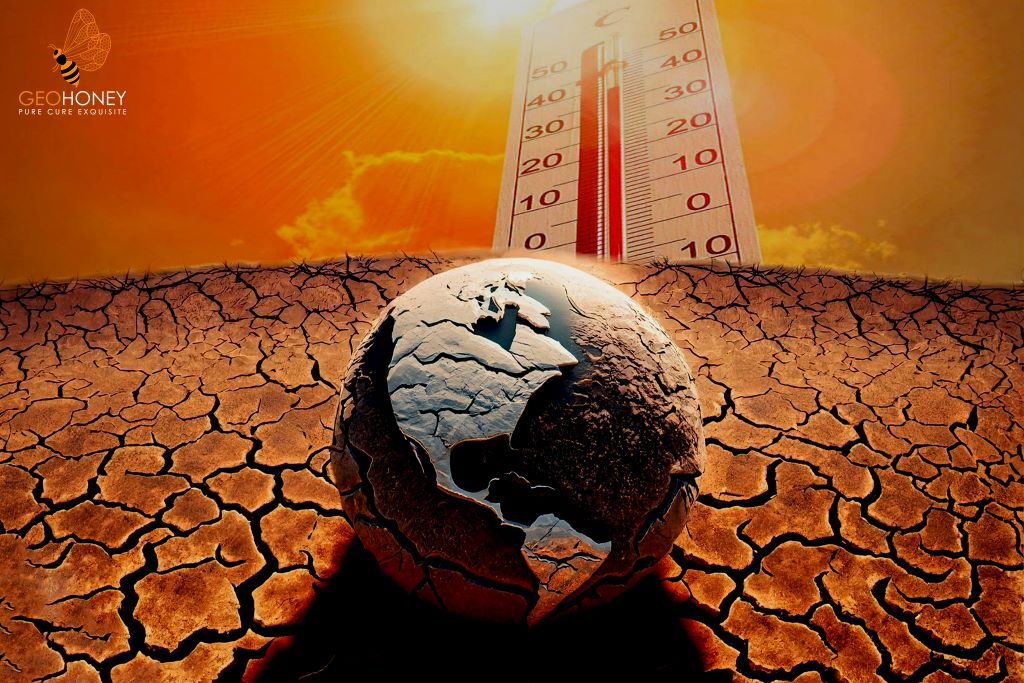

The Earth's First Experience at 1.5 Degrees Celsius

The world has now had its first true taste of a globe that is 1.5 degrees Celsius — or 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit — hotter than it was before the Industrial Revolution.

According to Copernicus Climate Change Service data, July of this year was the hottest on record, measuring 1.5 to 1.6 degrees Celsius hotter than the norm before the widespread usage of fossil fuels.

"It's just shocking how far this is from anything we've seen before," said Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist and the climate research director at the payments business Stripe, noting that July was 0.35 degrees Celsius warmer than the previous record.

Prior to this July, the world had momentarily exceeded 1.5 degrees Celsius a few times previously — but it was during the winter months for the Northern Hemisphere, so the effects on the biggest population centres were mitigated. This was the first month in which temperatures were above pre industrial levels, and the majority of the world's population was experiencing hot, summer conditions.

This does not imply that the world has failed to meet its climate objective of avoiding a temperature rise of more than 1.5 degrees Celsius. That would necessitate average temperatures above that level for numerous years in a succession, rather than simply a single month. Scientists currently believe that unless drastic emissions reductions are implemented, the 1.5 level will be reached by 2030.

However, it does mean that people all over the world have had a small taste of what it may be like to live on such a planet during the summer months. It hasn't been easy. Temperatures in Phoenix exceeded 110 degrees Fahrenheit for 31 days in a row, occasionally reaching 118 or 119 degrees. For the first time since the coronavirus pandemic's peak, the local medical examiner's office was compelled to bring in refrigerators to manage surplus bodies.

In Europe, Rome set a temperature record of 107 degrees Fahrenheit, while inhabitants in Beijing purchased full-face masks known as "facekinis" to protect themselves from the sun. The heat index in Iran's Persian Gulf reached 152 degrees, which is close to the limit of human survival.

On some level, this is unsurprising. According to scientists, July's blazing temperatures are in accordance with what is expected in a climate-changed planet. "This is within the range of our models," said Andrew Dessler, a Texas A&M University climate scientist.

Some present aspects of the climate system, such as the record-low Antarctic sea ice, are actual anomalies that scientists are unable to explain. However, the majority are exactly what we would anticipate from a civilization that has continued to consume fossil fuels. While some rich countries have reduced their usage of coal, oil, and gas, worldwide emissions have remained stable. And the planet will continue to warm unless global emissions are reduced to zero.

One of the most frightening aspects of the approaching warmer world is how rapidly people emotionally adapt to it. Almost ten years ago, 2014 was the warmest year on record; now, in retrospect, 2014 appears pleasantly chilly. Researchers discovered that humans quickly stop commenting on scorching temperatures; after two to eight years, what was previously a record high becomes the new normal.

While certain parts of rising temperatures may become routine, others will not. Temperatures in parts of the Middle East and Africa are approaching the limits of what human bodies can withstand. At the same time, as temperatures climb above what was designed and planned for, electric grids, roads, bridges, and other infrastructure are under strain. "What we're seeing is that our world is very sensitively designed for a very small range of temperatures," Dessler explained. "When the temperatures rise above that threshold, the entire system implodes."

The 1.5 degree Celsius milestone is not a magical tipping point; scientists are unsure whether it will cause certain thresholds to be crossed. However, it represents the hope of world governments to keep climate change under control. And the potential consequences worsen with each slight bit of warming. "The next tenth of a degree is going to be much worse than the last tenth of a degree," Dessler predicts.

Source: washingtonpost.com